The tea had cooled, but Subramanyam hadn’t noticed. His mind was still circling that one word, ‘clock.’ It sounded poetic in the way the doctor described it, but Subramanyam’s world had been built on hard numbers and facts, not metaphors.

“So, Doc,” Subramanyam said finally, leaning back, “this master clock thing… it sounds like a TED Talk headline. Is there actual science behind it, or is this just another wellness fad dressed in white? ”

Dr. Biswajit chuckled softly, the kind of laugh that belongs to someone who’s been asked the same question by skeptics too many times. “Fair question,” he said. “Let me take you back… not to a boardroom, but to a fly.”

Subramanyam raised an eyebrow. “A fly?”

“Yes,” the doctor said, his eyes glinting with the thrill of storytelling. “In the early 1970s, a scientist named Seymour Benzer started studying fruit flies. He noticed something fascinating—these tiny creatures had a rhythm. Even when kept in total darkness, they still behaved as if they knew when day and night were happening. They had an internal clock.”

Subramanyam frowned. “So the fly kept time without a watch.”

“Exactly,” the doctor said. Fast forward to 2017, three scientists, Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael Young, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the genes that make this clock tick. They called them period genes—PER for short.”

“PER… as in periodic?” Subramanyam guessed.

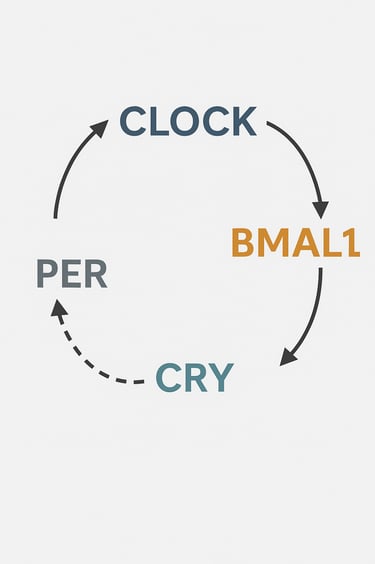

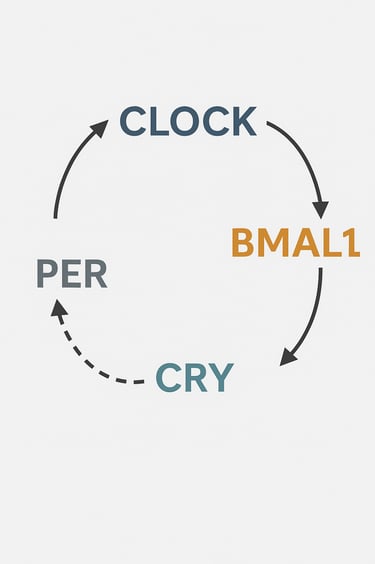

“Yes,” the doctor nodded. PER works with other genes like CLOCK and BMAL1 to create a feedback loop inside your cells. These genes produce proteins that rise and fall in 24-hour cycles, controlling when your body releases hormones, when your liver digests food, when your brain sleeps, and when your cells repair DNA. You are literally wired to the Earth’s rotation.”

Subramanyam stared at him, incredulous. “And all this… is happening inside me right now?”

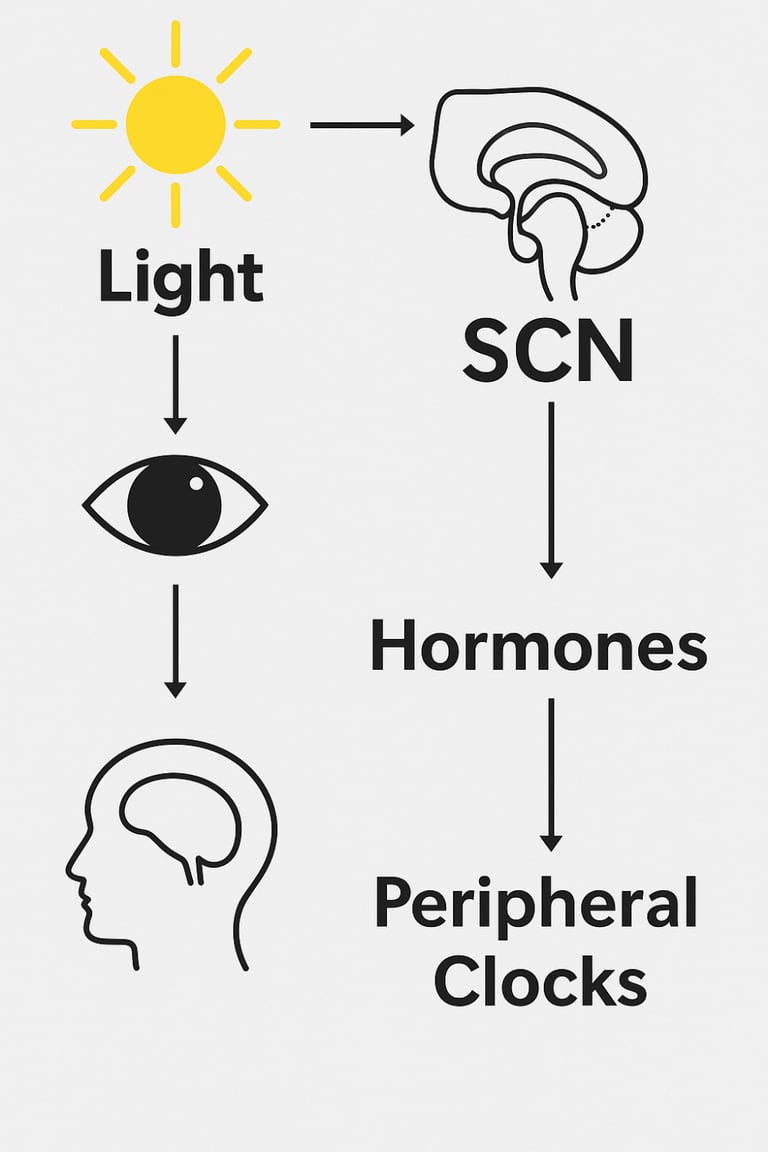

“Every second,” the doctor said. “Your suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN, in the hypothalamus, is the master conductor. It takes signals from light entering your eyes and synchronizes every clock in your body—your heart, your pancreas, even your skin cells.”

Subramanyam let out a low whistle. “And I thought my biggest synchronization problem was aligning meetings across time zones.”

The doctor smiled. “Your time zones were inside you all along.”

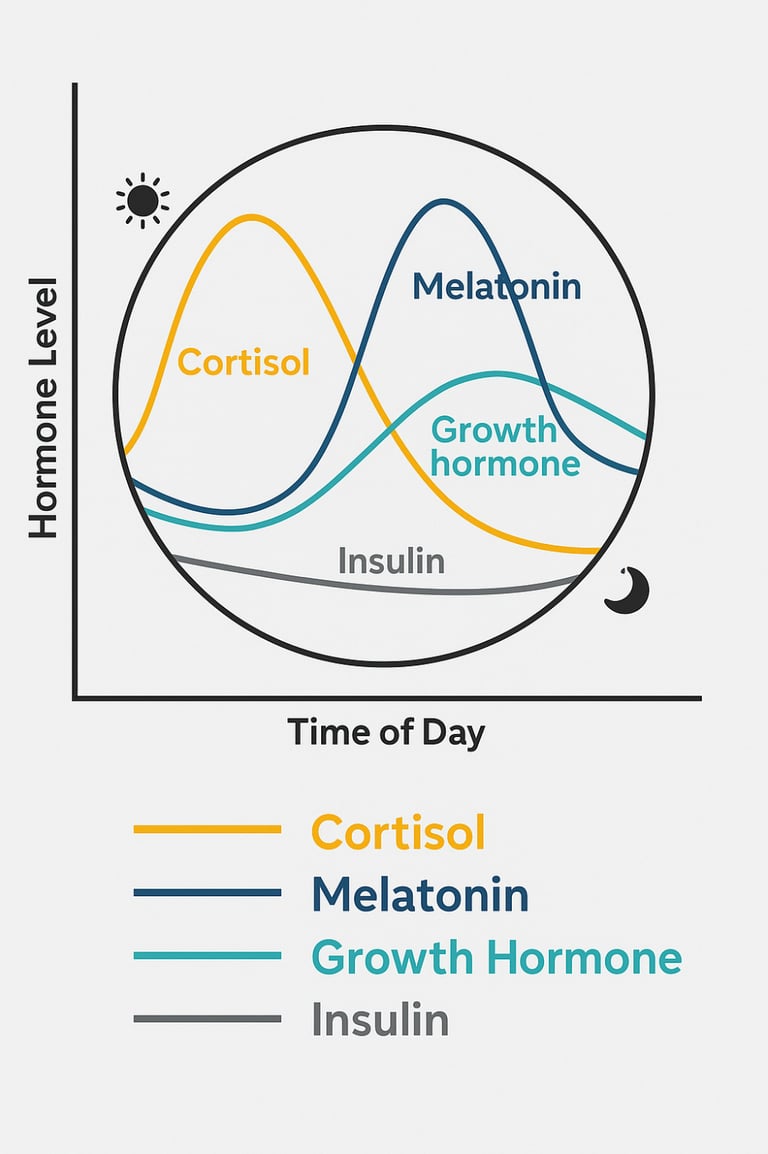

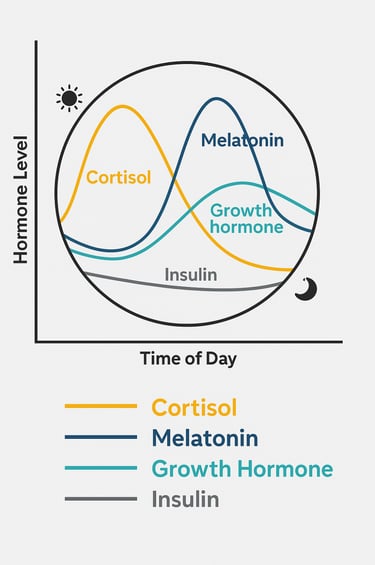

“Imagine this,” the doctor continued, “at dawn, your cortisol peaks, waking you up. By mid-morning, your brain’s alertness is at its sharpest. In the afternoon, your physical performance hits its peak. As evening approaches, your body temperature drops, preparing you for sleep. At night, melatonin floods your system, telling your cells to repair, restore, and detoxify. This rhythm isn’t random; it’s precision engineering by nature.”

Subramanyam leaned forward, curiosity sharpening his tone. “So what happens when someone… like me… ignores this rhythm? ”

The doctor’s face turned serious. “Then the orchestra falls apart. Your pancreas may release insulin when your liver isn’t ready to process glucose. Your stress hormones surge at night when they should be low. Your gut bacteria lose their rhythm, causing inflammation. Over time, this chaos can lead to metabolic disorders, depression, immune dysfunction, and yes—even cancer.”

Subramanyam swallowed hard. “You’re saying my late-night deals and 2 a.m. emails… they weren’t just bad habits—they were… carcinogenic?”

“Let me put it this way,” the doctor said gently. “In 2007, the World Health Organization classified night-shift work as a probable carcinogen. Disrupting your circadian rhythm isn’t just unhealthy—it’s dangerous.”

Subramanyam stared at the rising sun, the golden light washing his face. For the first time in years, he felt something other than control. He felt… awe. And maybe a little fear.